HOME | home

Folk Music Index | Christmas Carols | The Celtic Christian Tradition | A Shepherds Songbook | Celtic Christian Links and Lore | Christian Thought | Being 'spiritual but not religious'? | The Ten Commandments | The Good Shepherd | Christian Communities in Peril | Humanism | Jesus and Reason | The Great Fundamentalist Hoax | Why This Scientist Believes in God | My Problem with Christianism | Who Owns Christianity? | Blood Thirsty Christians??? | Birth and Death | Celtic Christians | Celtic Crosses | Women in the Church | Christ by William Dyce | Stobo Kirk | Psalms of David | Saint Clement's Church | Rossyln Chapel | The First Presbyterian Church | Hurlbut Memorial Community Church | Christmas Eve 2009 | Photos of Church Activities | Postcards of Hurbut Church | Hurlbut Photos | Hurlbut Photos 2 | Hurlbut Photos 3 | Pentecost Sunday 2010 | Annual Picnic 2010

Celtic Christians

Introduction to Celtic Christianity

- by Caedmon Greene

Celtic Christianity was that form held by much of the population of the British Isles from about the end of the fourth century, until some time after the year 1171. Like any church it varied in form, from place to place, and time to time. However there is a constant stream that runs through that identified it as an unique entity. The classic period of Celtic Christianity ran from the fifth through the ninth centuries, in the "traditional" Celtic Lands (Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and Brittany) on the continent (France, Spain, Italy, Switzerland, and Germany) and beyond (Iceland, the Farroes, and other North Atlantic islands perhaps in Russia and North America).

Celtic Christianity was characterised by extreme holiness, a love of God and man, and wanderlust from the need to bring the light of Christ to the world. Also, many of the issues that the Celtic Christians dealt with are amazingly contemporary - things like the position of women in the Church, nature and our environmental surroundings, and dealing with others of different customs and beliefs (both pagan and Christian). Much of its attraction comes from how it dealt with these problems, taking the best from older traditions while still standing firm in the truth.

Tradition holds that the faith was brought to the British Isles by Joseph of Arimathea and Aristobulus in A.D. 55 (some argue it was as early as A.D. 35) [Some] modern scholarship rejects this, and place the introduction in the middle of the second century. Little is known of the first several centuries, however, Christianity was firmly established in Roman Britain by the time of the council of Arles (314) as two British bishops were in attendance. (There is also a possibility that British bishops were at Nicaea).

The true flowering of Celtic Christianity occurred after the Romans left Britain and they found themselves alone, surrounded by hostile barbarians. This is the time of the great celtic Saints: Patrick, David, Brigid, Columba, Brendan, Columbanus, and many, many others. This period was characterized by great holiness, love of learning and nature. It reached it's peak in the seventh century in the Columban monastic federation of Iona. Its decline began soon after when, in 671, it lost Saxon Northumbria to the Roman observance.

This was by no means the end. Celtic Christianity survived for the next five centuries. Due to many forces, demographic changes, Viking raids and settlement, and the expanding Roman rite; Celtic Christianity slowly retreated. Yet this was the period when the Celts reached the pinnacle of their artistic genius; combining mediteranean plaitwork, barbarian zoomorphs, and their own native spiral and key patterns to create metalwork, illuminated manuscripts and stonecarving that amazes us even today. (Some examples include the Kells and Lindisfarne Gospels, the Ardagh Chalice, the Tara brooche and the Linsmore Croizer.)

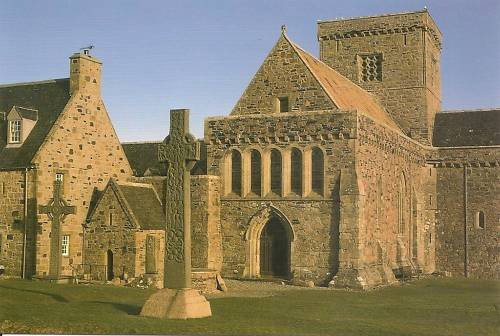

Sacred Isle of Iona

Iona. The monastery founded by St Columba in 563 soon became the centre for Celtic Christianity, sending out missionaries to Scotland and Northumbria. Although the ravages of Viking raids before and after 800 made Iona a more dangerous place to live, its prestige continued well into the 9th cent. Following a massacre of its monks in 806, work began apace on the Irish midland monastery of Kells, which was gradually to become the focus of the Columban communities in Ireland. Kells was finished in 814, and not long after (c.818), a new Columban monastery in central Scotland was founded, Dunkeld. It is generally held that in 849 the relics of St Columba were split between the two new monasteries, confirming shifts in patronage and power centres which had been under way for some time. From the end of the 9th cent., we find the head of the Columban communities, the comarba Choluim Chille, based in Kells, and the headship remained there until the 12th cent.

None the less, Iona's importance as a religious centre continued, and began to attract the newly converted Norse settlers of the Hebrides. Two Norse cross slabs are now housed in the Iona museum, one bearing an inscription in Norse runes, another bearing a scene from Norse legend. In 980, the powerful king of Viking Dublin, Olaf Cuarán, died on pilgrimage to the island. This was an up-and-down relationship, however, as six years later, a raiding party from the Northern Isles slaughtered the elders of the monastery and the abbot.

The wider influence of Iona monks can be seen as far afield as Carolingian Europe. Dicuil, a cosmographer who wrote a description of the world c.825 in the court of Charles the Bald, probably came from Iona, and he describes other Iona monks ranging as far north as the Faroes and as far south as Egypt. The martyrdom of Blathmac, son of Flann, defending the relics of Columba from Viking raiders in 825 caught the imagination of Walahfrid Strabo, based in the monastery of Reichenau on Lake Constance. One of the 10th-cent. heads of the Columban communities, Mugrón (965–81), who appears to have been partially based in Scotland, was a devotional writer of some skill.

The 11th cent. was marred by such incidents as the loss of some of Columba's relics on a journey back to Ireland from Iona (in 1034), and slaying of the abbot by a rival, the son of a former abbot of Kells in 1070. None the less, Scottish kings, according to tradition, continued to be buried there, and Margaret, wife of Malcolm III, king of the Scots, held the monastery in favour.

In the next century, it again became the religious hub of a new island-centred power-base. Somerled mac Gille-Brigde, the powerful Argyll sea-lord whose descendants became the Lords of the Isles, attempted in 1164 to lure the head of the Columban communities back to Iona. He failed, but the building of a new Benedictine monastery in 1204, followed by an Augustinian nunnery, spelled the return of Iona's fortunes. Closely linked to the Lords of the Isles from the 14th cent. onwards, and the seat intermittently of the bishop of the Isles, Iona in the later Middle Ages was a great centre of sculpture. The present church on the island dates substantially to the 15th-cent. renewal programme, and displays the skills and patronage then available. Only with the forfeiture of the lordship in 1493 and the Reformation did Iona's decline set in in earnest.

-Thomas Owen Clancy

LINKS

Deep peace of the flowing air to you

Deep peace of the running wave to you

Deep peace of the quiet earth to you

Deep peace of the Prince of Peace be upon you

Suggested Readings

The Celtic Way of Evangelism

by George G. Hunter III

Holy Ground

by Deborah K. Cronin

Anam Cara: A Book of Celtic Wisdom

by John O'Donohue

Celtic Christian Spirituality, an Anthology of Mediaeval and Modern Sources

by Oliver Davies and Fiona Bowie

Listening to the Heartbeat of God, A Celtic Spirituality

by J. Phillip Newell

The Celtic Vision

by Esther de Waal

The Celtic Saints

by Nigel Pennick

Celtic Prayers

by Robert Van De Weyer

The Celtic Year

by Shirley Toulson

Every Earthly Blessing, Rediscovering the Celtic Tradition

by Esther De Waal

Celtic Blessings and Prayers, Making all things Sacred

by Brendan O'Malley

Celtic Blessings, prayers for Everyday Life

by Ray Simpson

Gum beannaicheadh an Tighearna thu, agus gun gleidheadh e thu:

Gun tugadh an Tighearna air a aghaidh dealrachadh ort, agus biodh e gràsmhor dhut:

Gun togadh an Tighearna suas a ghnùis ort, agus gun tugadh e sìth dhut.

May the Lord bless you and keep/protect you,

May the Lord reveal His face unto you and have mercy.

May the Lord turn His Face unto and give you peace.